Artists are expected to go through periods or phases, among other things they go through. I had a roughly 20-year watercolor phase, with venues mostly in Southern California and St. Louis, usually en plein air. This book is witness to it. It is also expected that artists be influenced by certain master artists, and that these influences be acknowledged. Touted, more accurately. This book does that too.

I had drawn since before I can remember, but this was my first painting phase. Starting when I was 15 or 16, that would be circa 1944, it ended, never to return, when I was in my thirties, in 1963. That was a long time ago -- I am now 84.

When I began painting watercolors it was still the Golden Age of California Impressionistic Landscape painting, of a narrow range of subjects and style -- foreground stage-curtains of eucalyptus trees, middle-ground meandering arroyo and fields of poppies, and the obligatory almost translucent purple mountain background, no human beings anywhere; oil paintings with Monet daubs or short Cezanne strokes. As a child I was taken to the long-gone art wing of the Museum of History Science And Art in Exposition Park in Los Angeles, to view exhibitions of the legendary landscapists such as William Wendt, Granville Redmond, and Paul Lauritz. Those oil painters, the first I’d seen in my life, inspired me to paint landscapes like rock stars inspire kids to lambaste drums nowadays, but didn’t influence my style or technique much. I was doing watercolors, not oils.

Oils and watercolors are as different as oil and water. Oils are accreted on top the canvas like stalagmites, they grow from canvas like oak trees. Watercolors dive into the paper and live inside it, like jelly fish in the sea. Watercolors are frail, pallid, picky, peaked petunias and sweet peas in washed-out vases. That’s the familiar kind, so charming to the elderly. But watercolors can be impetuous, manly, kinetic, broad and broadly painted with flat brushes preferably an inch wide, with paint in tubes, not blocks. It’s that kind I aspired to. Eisele Galleries in Cincinnati, which handles my whole oeuvre, describes my style as quick and fearless, controlled and confident, loose and literal. Hmmm… what happened to “charming”? Truth in advertising, for once.

Oils are for the ages -- taking ages to accomplish, certainly to dry. Watercolors are caprices, cadenzas, riffs, improvisations, quick little jigs, one-hour stands, that’s the charm of watercolors. And that is exactly what appealed to me in youth. That is what youth is for. I haven’t done a watercolor in 50 years. I’m not sure I could, not with the old recklessness, or want to. That’s not what old age is for.

Hmmmm. What happened to acrylics? Everyone asks me that. I’m so old I began my watercolor phase before acrylics as an artist’s medium were invented, certainly not marketed. Besides, my virtual mentors, Kautzky and Kosa were even older and had never heard of acrylics. In recent years I’ve given them a try. Just plain wrong for my technique. They’ve taken over now, but weren’t available back then – lucky, lucky me! Anyway, my 2nd painting phase, 30 years later, would be oil paints, with alkyds, brand new.

Meanwhile, I was in school year-round pursuing an accelerated double-course program to make it into medical school before draft-age (18), then medical school and specialty training and research, finally military duty, and then practice of internal medicine (we still did housecalls), and I simply didn’t have the time to do oil paintings. But for watercolors 45 minutes, at most an hour, is all you need for a great finished painting, or a mess, and that’s that. I didn’t have any choice but to go with watercolors.

If one is self-taught, as I essentially am, oil painting is best learned by seeing and copying original paintings, not from reproductions, which hardly begin to recapitulate the originals. But reproductions of watercolors do, amazingly well. And reproductions of watercolors were all I had.

My mother had given me great watercolor books to study, The first such -- I don’t remember not having it as a kid, and poring over it, copying the plates as Sargent did Velasquez’s originals in the Prado Museum in Madrid; I still have it within 5 feet of where I sit and do not feel secure about life unless I know it’s still there, but haven’t cracked it for maybe 40 years -- was Ways with Watercolors, Ted Kautzky, Reinhold Publishing, 1949. His dry brush style, disciplined by his classical training in architecture in Hungary, resonated with mine and awakened it.

None of my study copies of Kautzky are in this book. Copies of nobody are. Everything in this book is a Kime original.

I also had a book by Emil Kosa, whose style was akin to Kautzky’s and creditably academic, when he wanted. But, not surprisingly since he was a movie-studio artist, though I’ve always supposed he was as much influenced by Thomas Hart Benton as Hollywood, he saw Southern California from funhouse mirrors -- inebriated houses, staggering fences, and quasi-humanoid shapes bent against the wind. So, not surprisingly, he is considered a founder of the “California style” school of watercolor. It would be 30 years before I would become familiar with Sargent’s famous sopping wet-into-wet watercolors.

But Kautzky painted Old New England and the quaint fishing villages and well-ordered old clapboard cottages and the lush, wet countryside blazing gold and scarlet with maple and oak trees. It was these scenes I copied. Lovely, those scenes, but alien to me. Kautzky’s style didn’t work for San Pedro harbor (LA’s port) or the dusty eucalyptus and palm trees I was seeing. Meanwhile Kosa lived where I lived and saw what I saw. and was painting San Pedro Harbor and rustic Chavez Ravine long before Dodger Stadium, bent telephone poles and bowed people and all. So to start my watercolor phase I followed Kosa to San Pedro Harbor, then cluttered with costal freighters and surplus minesweepers from WWII. On the way there I passed Chavez Ravine but didn’t stop.

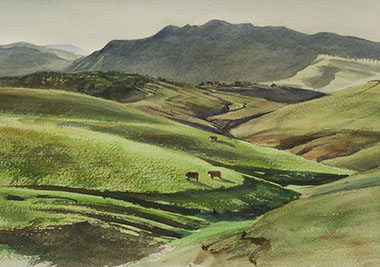

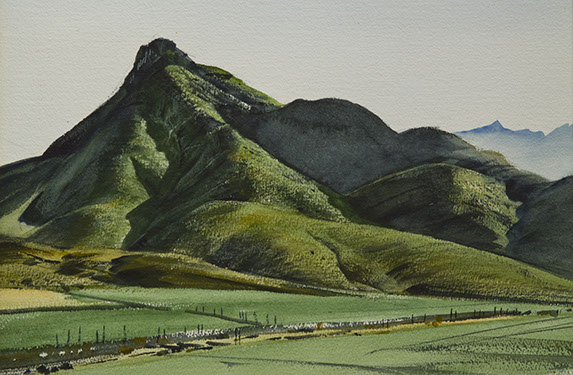

But what I really wanted to paint were certain hills that I’d seen in Lauritz’s oils -- Long, slow rounded smooth rolling hills, streamlined, dimpled rather than gouged and in places finely corrugated by sheep trails, and essentially naked of growth except grass, their young feminine forms exposed and flaunted, rhythmic ranges of those hills blazing purest green, in the late afternoon boldly patterned by sharp, long, parallel black-green shadows like flaccid iron bars laid from east to west across the shapes and the canvas. Pure shapes, patterns, design: of all artistic elements that the human eye can behold, these elements have always most strongly fired me up, taken me over. They are felt somewhere within the mind, not just seen, and they wind up all over deep parts of the brain. The Golden Age California landscapes opened my eyes, but only Lauritz and his special hills, fantasy hills, pinup hills, popped my eyes. It was those hills that I wanted -- I’d have to say lusted -- to paint.

Where had Lauritz found them? There are plenty of various kinds of prominences and outcroppings all around, jagged, eroded, old and wrinkled. The rounded, fluid kind did exist but were at least an hour’s drive from where we lived, and rare even there, and as fugacious as falling stars. For only a few days of the year, in March, the tall brave grass of the otherwise essentially barren Southern California hills is dazzling green, and as instantly dead gray, the fantasy vanished. Don’t blink your eyes. Talk about unsustainable! And besides, for painting I had only occasional afternoons off, and had to start driving back home before the traffic turned bad and the lighting turned good. I wound up with more paintings of stark semi-desert than of exuberant green hills, and I settled for, if I was lucky, backlighting and patchy cloud shadows blotching the earth like a Holstein cow’s hide.

In any case, now those rare hills don’t exist at all. Overrun by houses and jacuzzis like Egypt overrun by locusts; buried under Walmarts and Jacks-in-The-box, infrastructure and interstates, litter and activists, Lauritz’s hills are history, like ancient Troy. In anticipatory vengeance, also because my heroes of the Golden Age of California landscape were misanthropes and excluded humans from the picture, I extirpated from every watercolor of hills every last human being, even Indians (unless they were trudging), or evidence of such, except old fence posts. The posts always cast long shadows.

Also vanished from the earth are Lauritz’s paintings of those hills. They are unknown to, say, the Redfern Galleries or the web. I’ve checked. The Lauritzes you will be shown by galleries specializing in Golden Age landscapists are his famous seascapes or clones of Wendt’s eucalyptus trees. Lauritz’s Green-Hill phase was as fugitive as the grass he painted. I saw them with my own eyes, and blinked and they were gone.

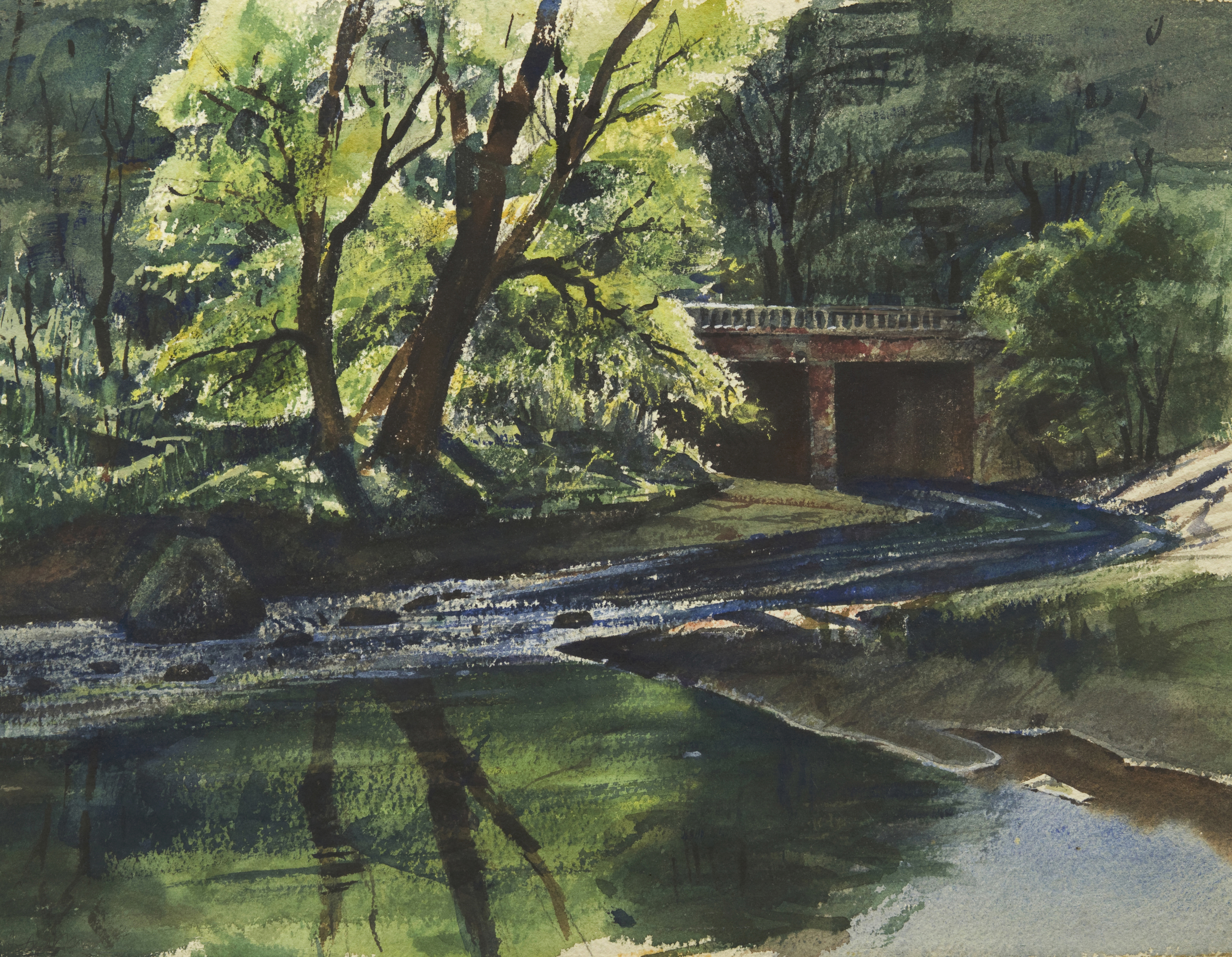

Anyway, I moved to St. Louis in 1958 for a research fellowship at Washington University and found the city grossly, even grotesquely, unlike anything I’d known in Southern California or the California Golden Age of Landscaping, but as compelling. Adding a bizarreness to the artistic charm of the unfamiliar weathered Italianate stores and shops and once opulent neighborhoods of brick and stone, it was being demolished.. In fact it was demolished twice. The huge Pruitt-Igoe Housing project for the indigent would arise there, a utopia. As utopia it would prove as unreal as Lauritz’s green hills. In the 1970s the whole business was imploded in one instant -- boooUM! -- not a decade.

But in 1958 I found the first demolition in plodding progress. A row of townhouses would be demolished and cleared away, all except one last house still standing alone on the bare reclaimed litter-free earth, among the weeds. Parts of tenement houses would be neatly sliced away leaving exposed papered walls patterned by imprints of studs and stairs, frozen to still-intact neighboring buildings. Freestanding jagged walls rising from rubble like chips of white chocolate on end on a bed of jelly beans. Whole new vistas were opened -- the hard way. A war scene, from the war on poverty as it happened, of political interest to most people, but to me, normally obsessed by politics, of overriding artistic interest, surrealistic, seductive and I couldn't help it. And it was the era of billboards and TV antennas, as crucial elements for surrealism as limp clocks, not yet blighted by graffiti. Kosa would go crazy here.

Just about every Sunday after checking the lab I would make a painting foray out there, pull over anywhere and park, scoot over to the passenger seat, and, with my painting board on my lap, splash away, oblivious to the dangers Tom Wolfe would depict in Bonfire of The Vanities. I wound up with an oeuvre as surrealistic as Dali, replete with Kosa’s cockeyed telephone poles and chimneys, funhouse-mirror rooflines, and always the same long-coated person trudging the otherwise deserted streets (not as a social protest message but to give motion), even Kautzky’s wet gleaming ruts and tarpaper roofs -- but unsalable. Eisele Galleries must have lost money on them, despite presenting them as “architectural renderings.”

In any case, my watercolor venues are gone, my watercolor phase long gone. But I still use my 1-inch Kolinsky sable brush for, at last, blending oil paints -- 20 years of studio portraits, not plein air landscapes. And of the stack of 50 sheets of d’arches 550 lb rough cold-press watercolor paper, breathtakingly expensive (at today’s price, discounted, about $1,000), that my dad bought me 70 years ago, I still have 14 full sheets left. I’ve just now recounted them.

my w a t e r c o l o r phase