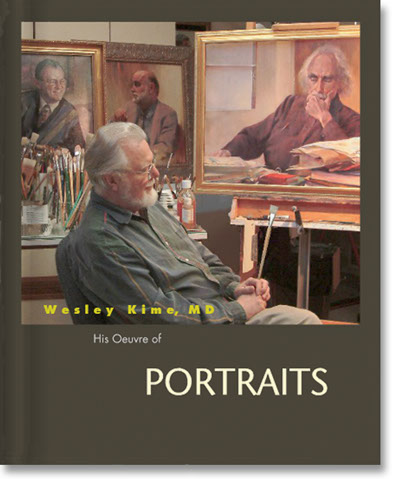

This is a book of portraits in oil painted by a physician, me. That’s not quite as odd as oil paintings by Hitler, but odd enough to warrant a preface, pages of preface, in lieu of my memoirs, such as all my octogenarian friends are writing. It all began, as memoirs always begin, when I was born, no, squeezed out of a tube of Grumbacher oil paint. When I entered medical school at 19 I had already been pursuing art for at least 15 years.

This is a book of portraits in oil painted by a physician, me. That’s not quite as odd as oil paintings by Hitler, but odd enough to warrant a preface, pages of preface, in lieu of my memoirs, such as all my octogenarian friends are writing. It all began, as memoirs always begin, when I was born, no, squeezed out of a tube of Grumbacher oil paint. When I entered medical school at 19 I had already been pursuing art for at least 15 years.

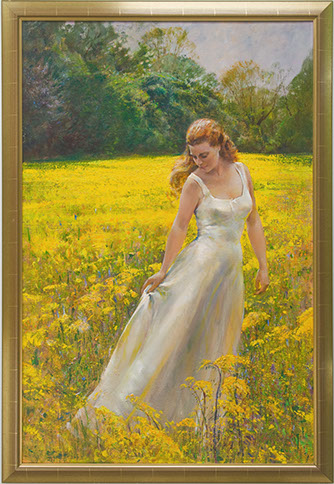

As a small kid the first thing I wanted to paint was landscapes. But a career in medicine would coop me up in buildings where I would see people, not purple hills. People would be my art, at first by default, then by desire to a degree inviting psychiatric analysis. To paint medical illustrations, like Frank Netter, MD, never occurred to me.

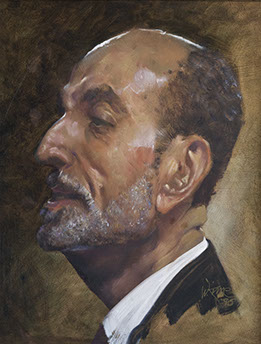

Frameable finished oil portraits in the studio at a big easel, like Sargent, is what I yearned to do. That had to wait 50 years until I retired at age 65 and walked out the office and closed the door behind me never to look back. Meanwhile I settled for, and relished, quick 15-90 second surreptitious but hardly secret fountain pen sketches of my unwitting or nonplussed subjects -- fellow students, teachers, people lounging at airports or restaurants or in church pews or committees. The years rolled by and my fresh-faced subjects ripened, to my glee, into character studies. A gleaming bald pate with so many reflecting planes and subtle colorations is a more paintable still life than a patinated brass pot.

Legendarily, an arty kid sequestered in a classroom closes his eyes and doodles galleons, castles, pirates, or dragons, usually winged. Me, I had my eyes fixed on the professor and was sketching him, too much as a caricature but never a dragon. Maybe it would have been less disruptive in Executive Committee had I gone dreamy and doodled castles with wings.

My peculiar compulsion (“passion” if you must) is to paint what my literal eye sees (people), not what my Inner Eye is conjuring, famously unrecognizable at best. Prevailing weltanschauung be darned, the deliberately honest, and expert, depiction of reality is the proof of genius, not disproof. Disproof is doctrinaire disdain of reality. Anybody can paint a blob with both eyes on the same side of the…the what? Is it a face? Only a da Vinci can paint a Mona Lisa. Being a painting pathologist instead of a painting psychiatrist, or painting protester, I eschew the symbol or avatar whether pink, purple, or political. If I wanted purple I’d paint purple hills, not purple people. I don’t yearn to go where no man has painted before; I yearn to go where Sargent went.

Medical school was my de facto art school, and the seminar my atelier, where I studied art as earnestly as any expatriate American or Russian art student in 19th century Paris. Strong on facial expression and weak on Michelangeloean musculature and let-it-all-hang-out creativity, my art school curriculum was not optimally balanced or classical. But, as schools go, especially nowadays, mine was pretty good. For 40 years I mentally shadow boxed with shadows, reflected light in shadows that I saw on the chairman of the Executive Committee or a pewmate, figuring how I’d do it with a real brush in hand. I learned things like how slouched shoulders, the main action in committee, can convey emotion as powerfully as lips or eyebrows, and impart compositional motion as well as sprinting legs, necessitating changing the vertical “portrait” format to the “landscape.” Such shoulder dynamics were totally unknown to the ancient Egyptians, who could draw only childish stick-person shoulders, and was never taught at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, where a shoulder is just the pivot for a discus-throwing arm. Besides, I was spared the art-school lifestyle. But hands I can’t do any better than an advanced hobbyist.

My only formal training at art school was one semester of night classes in portrait painting at the old Otis Art Institute in LA on Wilshire Blvd (still going strong). This was when I was interning, in 1952-3, at the old (now defunct) 3000-bed Los Angeles County Hospital, a savagely demanding business if there ever was one, duty every other night on the surgical and medical services, with up to 30 new patients, mostly emergencies like pulmonary edema or massive hematemesis or hemoptysis, undiagnosed cases of TB coughing in my face, and epidemics of acute poliomyelitis and people being rushed to iron lungs, up all night, no sleep. I was 23 and bemoaned that the LACGH was a sweat shop breaking all child-labor laws, which it was, judging by the drastic reforms imposed upon medical training since then. But I was young, a griping bragging top-gun, and strong to multitask. On evenings off I was at Otis Art, my art oasis. Then, finally, a lifetime later, in 1994, I segued self-trained into my 20-year career in portraits.

Career it is, absolutely, but for neither income nor acclaim. “This hobby is really fun for you, isn’t it?” I’m asked. “Fun?” I answer. “Somehow that’s the wrong word. The peace that passeth all understanding (Philippians 4:7), is more like it. Or torment beyond Dante. Hobby? … harumph!”

As single-mindedly as I had medicine, I poured over the chemistry, physics, and optics (skipped the spirituality and toxicity) of oil paint and painting, the books (historical art, anthologies and technical references), art magazines (most are for beginners), and videos (1-hour VHS apprenticeships with Daniel Greene, Burt Silverman, Richard Schmid), and field trips to art museums. I evaluated at least a hundred celebrated artists active in the last 150 years, (excluding the likes of Modigliani). Open minded, I looked at Impressionism and decided that it may offer something for landscape painting, for portraiture not much. Rockwell or Rembrandt? Sometimes. Nicolai Fechin? Naw. John Singer Sargent is my all-time paragon.

Most crucially, I had access to live models at the Cincinnati Art Club’s twice-weekly live model sessions, called the Rettig Sketch Group, a famous feature of the CAC since its founding in 1890. Finally, after 50 years of studying contingent subjects around the conference table, it would be models on posing stands, just what an artist who went to medical school instead of art school, needed. Plus, hired models display a certain paintable angst not found even in classrooms or IRS audits.

So, starting in 1995, on Monday afternoons, regularly and eagerly I would drive from Dayton (home) to Cincinnati, an hour each way. There, garbed in a paint-smeared rather than blood-spattered gown, and breathing in the lovely smell of linseed oil and real turpentine, I was at last in my natural milieu, among kindred arty souls, even if they cowered at all-natural turp and celebrated, in artistic innocence of chemistry, the odoroless highly-refined fossil-fuel global-warming kind. And I was standing forthrightly and exultingly at an easel, awkward to do at Tumor or Executive Board. Then, on April 6, 2007, halfway to Cincinnati, I became too tired, or something, to continue, pulled into an Odd Lots parking lot, turned around, drove back home, ending one of the happiest – and funnest -- periods in my life.

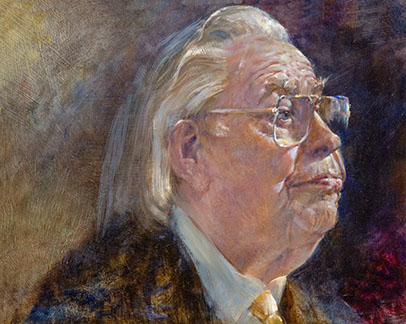

And Loma Linda University, my medical school, came back into the picture. If a half century ago LLU had provided unwitting models to sketch, the university now presented officially designated subjects, cooperative if not eager, for a series of finished and framed oil portraits, complete with official dedications with speeches and yankings of black curtains. A 10-year undertaking, the longest single project of my art life, the LLU series became my über-oeuvre, my Sistine Chapel, for me what the Boston Public Library murals were to Sargent.

At first I aspired to attack the canvas like Sargent, with the broadest brushes, preferably bristle brights, in bravura, kinetic, whaling strokes as calculated, and studied and purposeful as a NFL football play, not to be confused with the demoniac theatrical flailings in the movies. Though not wallowing in itself like Impressionism, the bravura technique isn't bashful about brush strokes and selectively and prudently displays stroke texture, throwaway strokes to give you the picture, not to take it over. It’s called alla prima … for prima donnas. Like me. That was my style at the Rettig Sketch sessions, to the bemusement and alarm of my easel-mates, probably muttering “show off!” under their breath. I could finish an oil portrait sketch in 45 minutes and be out the door by the second break.

But that, as I had learned at Otis, is not Rembrandt’s technique – multiple impasto strata of white underpaint surmounted by a thousand colored glazes -- yielding luminosity and depth not obtainable even by 3D inkjet printing.

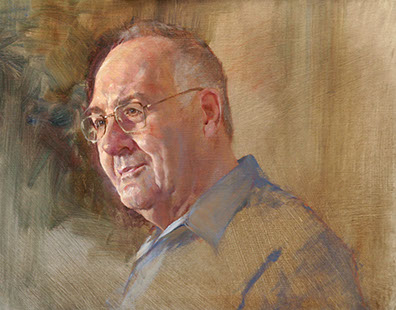

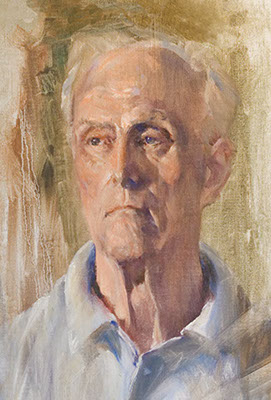

A third style is that of Bougeraux and the 19th century the Académie des Beaux-Arts, famous for proto-photorealism, detectable brushstrokes not allowed, on penalty of excommunication. Achieving that sort and degree of silkiness requires specially formulated slow-drying paint, brushes of soft fur from endangered species, and took centuries to perfect. The Impressionists famously and loudly rebelled against it. Nowadays, contemporary art schools and the high-rise, garret, and gutter worlds of art are contemptuous of the very idea, and it wasn’t taught at Otis Institute even back in my day, at least not in night class. It’s a lost art. I naturally and instantly had taken to bravura alla prima, but it took me nearly 20 years of solitary fiddling before I acquired a semblance of Academic polish and finish.

As I lost my rambunctiousness and finally acquired some skill in detailing, the 19th century academic blending mode combined with 17th century Rembrandtean glazes evolved into the style, unique to me, that I employed for the six heroic-size commemorative paintings hung in the Dean's pavilion at my medical school. Photorealism is timeless and still the most appreciated by my medically erudite but artistically innocent viewers, bless them.

Taking oil painting at least as seriously as examining specimens and composing biopsy reports for surgeons, I kept a log of every oil painting I painted, with records of the grounds used, palettes and mediums, the value key and style being aimed for, progress notes, and self-critiques as judicial as autopsy reports. But now a tongue-in-chichi critique of my whole portrait oeuvre is in order:

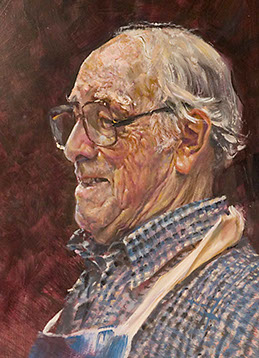

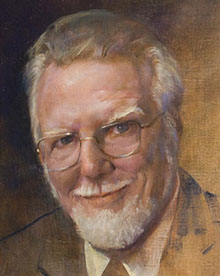

Arguably, Kime is as good as any living painter at relentlessly clinical likenesses, lentigos, nevi, bellowing platysmas and all -- he should have been a medical illustrator -- flattery be damned. Inarguably the result of 70 years and thousands of 30-second sketches from life in class and committee, Kime's background is matched, or sought, by few. Ironically, this comes through as 2 distinct portrait styles, depending on whether he is working from a virtual model -- a gelatin or electronic image -- which can be caught animated but is dead in 2 dimensions, or a real live model, frozen of visage but emanating a 3-dimensional power. When dealing with virtual models, Rockwell or Daumier seem Kime’s strongest influences; with live models, Sargent or Schmid. Thus what predominates in Kime’s CAC sketches of live models is sureness and certainty, and nonchalance, of brushwork, with hints of his signature facial expressions showing through. Sketches they are, none more than 3 hours, plus sometimes 3 more groping hours the next day. Sargent required of his live subjects 5-15 settings of 3-5 hours each. It will never be known what Kime could have accomplished thus advantaged. Obviously he works best from real life, disdaining painting from photographs, but having no choice for his LLU series. Thus this series shows the Kime informality and caprice, but is manifestly calculated and photorealistic. Accomplished but unsellable, not for what they are worth anyway, these could only be donated. LLU is thus endowed with a galley of portraits unlike those of any other medical school. He doesn’t do commissions, couldn’t, foolish idea.

Anyway, this 20-year oeuvre is composed of 500 paintings, 450 portraits, the rest seascapes and landscape sketches. 290 of the portraits were done at the CAC.

The CAC paintings, just studies done for practice, plus another batch done at odd venues, plus my whole oeuvre of watercolors, were purchased by Eisele Galleries in Cincinnati when we left Ohio in 2009. Mr. Eisele drove to Dayton from Cincinnati in a van and wrote a check for $5000 for the lot, “because,” he said, “of their quality." But who would buy a portrait of an unknown somebody, painted by an unkn own? Knowing they were unsellable, Eisele bought them anyway, bless him. By now, 2013, most have wound up on eBay or in dumpsters. Good riddance. On second thought, maybe even such casual paintings shouldn’t be lost to the world. Thus this book.

own? Knowing they were unsellable, Eisele bought them anyway, bless him. By now, 2013, most have wound up on eBay or in dumpsters. Good riddance. On second thought, maybe even such casual paintings shouldn’t be lost to the world. Thus this book.

The more privileged nearly 70 Loma Linda University paintings are hung at sundry venues on campus. Most have already been published, with full identification and biographies, as a hardback book, Portraits, Loma Linda University Honored Faculty, R. Herber, MD, editor, LLUSOM Alumni Publishers, 2005, or are available (currently) on the LLUSOM Alumni site, <http://llusmaa.org/paintings>. Thus this book contains only an aliquot, unidentified and presented for art's sake, not celebrity.

Soon to be hung in the Coleman Pavilion will be my latest and probably last painting ever. Nearing 85, my painting career is over. I have been thus informed not, as expected, by senile shakiness of hand – mine is as rock steady as ever, unexpectedly – or by my left eye being legally blind from macular degeneration, but by my Inner Eye, or something. I can’t explain why I ever painted, and I can’t explain why I won’t any longer. But… just this instant a new thing to try in my next painting popped into my head.