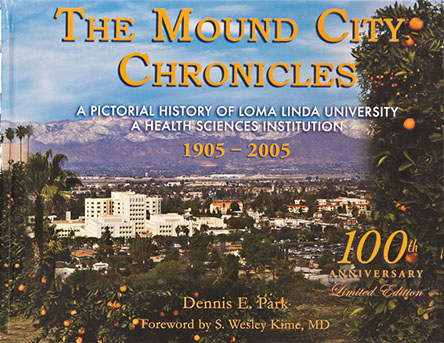

Published by Loma Linda University School of Medicine Alumni Association - 2007

Buildings  may not be the measure of a university -- its faculty and students are, likewise its purpose. And for LLU its service to God. But newer and bigger structures always going up reflects its progress and prosperity, a perfectly respectable parameter, and the one celebrated herein. In this LLU centennial year several publications will honor the University’s faculty, founding, past, and present. But this commemorative volume honors LLU’s buildings, the original ones, some long gone, some still standing unchanged or recycled, still revered or ignored, and the new ones, big, opulent, who could have dreamed of such buildings, and the better ones yet to rise.

may not be the measure of a university -- its faculty and students are, likewise its purpose. And for LLU its service to God. But newer and bigger structures always going up reflects its progress and prosperity, a perfectly respectable parameter, and the one celebrated herein. In this LLU centennial year several publications will honor the University’s faculty, founding, past, and present. But this commemorative volume honors LLU’s buildings, the original ones, some long gone, some still standing unchanged or recycled, still revered or ignored, and the new ones, big, opulent, who could have dreamed of such buildings, and the better ones yet to rise.

Dennis Park, a handsome man with the body of an NFL linebacker, the eye of an Ansel Adams, and the mind of a tribal historian, whom I think of as Uncle Dennis, wrote this book, as well he should. As Executive Director of the Alumni Association, Dennis for thirty four years has watched it happen, all the building, all the change, not only of LLU but also of the community of Loma Linda. He asked me, an old timer going back almost sixty years, to write the preface, wherein everything is blurred by faltering memory but sharpened by memories, blinkered by the perspective of an old med student, single back then, and tweaked by a caricaturist’s flourish.

Loma Linda was a college town, mostly college, where’s the town? There wasn’t much college either. It was still embryonal. The campus was a golf ball whacked off the green and lost in the sagebrush.

But the town already had a respectable main street, Anderson St., running bumpity-bump over the train tracks and curving around the base of the hill, the mound of the original Mound City. Barton Road was merely the newly paved byway that limited our known world.

My world was the med school campus. On the flat land abutting the mound across Anderson St., like a smallish camp of Israel beneath a smallish Mt. Sinai, it was primordial compared to the majestic domain now stretching on up the gentle slope to the south, and in the future down the slope to the north. A model campus, I mean like a model railway. There were just three Monopoly-board stops around the rectangular track, the anatomy, pathology, and physiology buildings. Plus Daniels Hall where I roomed with Bob Horner, a wry guy even then, and Burden Hall, then a chapel where Weeks of Prayer were held.

In those days the science buildings were not named for people. But the anatomy building was already famous for old professor Sam Crooks who, on the first day of school, clad in overalls, always supposed he would be mistaken for the janitor. He never was. Then he would present his famous collection of shriveled apples, mercy offerings of previous freshman classes.

That anatomy amphitheater was where we boys sweltered in white shirts and neckties, trying to heed lectures and taking notes (I drew caricatures), starting at 7:00 a.m., day after day. Just outside the door was the volley ball court, and between lectures the pent-up lot of us would burst out that door and take it out on the ball, whamming the daylights out of it, then retighten our ties and troop back inside and resume our languor. Volley ball was to CME in the days before there was a gym as football was to Eureka College in Ronald Reagan’s day

To us single med students it was fitting that when we raised our eyes from the campus to the hill the first thing we beheld up the slope, elevated like the New Jerusalem in the sky, was the student nurses’ dorm, with its own volley ball court, the prototypical and perfect singles mixer, where gentle maidens and show-off med students mingled and volleyed in the twilight, after supper.

Where we had had supper was probably in the nearby cafeteria in what remained of the original hotel from pre-CME days. I’ve just been looking again at grainy old photographs of that old building and wondering what to make of it. Theatrically perched on the summit of its own knoll commanding the valley, it brings to mind a King Ludwig, a Walt Disney, or a medieval castle, or, with those steps ascending forever, especially awesome from the railroad station at the foot of the hill, a Mayan pyramid. Wrong. Wrong architecture. Late 19th century generic Victorian, is what it was -- bristling with steeples and gables and snapping pennants and flags in symmetrical array, with a central dominating pagoda-like tower, wooden, very wooden, grandiose. Alien to our Loma Linda culture in any case, it was half gone by my time, its charm all gone. But I marvel at the view it had. I must say, if Loma Linda University has the vision, the Mound City Hotel had the view.

In my day the hospital was the San* further up the hill. But it wasn’t part of our world in those days when Loma Linda had only preclinical studies. If I happened to be up there, which wasn’t often, I would stop and study it, not because it was where patients were and I wondered what seeing patients would be like, but because the building looked so different from the rest of the campus. With the lovely and distinctively Victorian old hotel so reduced, the San was the one building with a hint of architectural style, a far cry from the no-thanks-to-bauhaus stark boxes of the campus. Lacking the grandiosity or the view the old hotel had, it was nestled into the hill among the eucalyptus trees, comfortable, red tile-roofed. It was, I figured, probably a combination of Mediterranean and early California Mission Revival styles, remaining unique to the hill and village to this day.

After making the around-the-hill curve, Anderson Street snaps to north-south grid. In my day the city center was already there, across the street from your fine stores and bank. But back then it was only two or three smallish conjoined buildings, of half-hearted art-nouveau style, a grocery store and vegeburger eatery, looking like something from an Edward Hopper painting, abutting the sidewalk and curb and one or two parked cars, maybe a Nash or a De Soto, with chrome bumpers, flimsy things.

Just across Campus St. from Daniels Hall, to the west, was a small faculty enclave of tidy 1920s gray cottages, appropriately devoid of ornamentation, with skinny sheds for garages. Those toy cottages were so small and simple that returning old grads, though familiar with them, are always surprised, and their families stunned. What stuns the old grads is that about a quarter of the neighborhood, including where the Harold Shryocks used to live, is just not there. Gone. Instead, there’s a huge alien slab of concrete, the parking garage, seemingly larger than the whole campus in the old days.

So humble were those faculty dwellings that when some of the dear old faculty grew old and moved to the new retirement Villas, they went upscale. By comparison the wave of 1950 and 60s residences with their two-car garages in the foothills are manors, and the 1980 and 90s 3-car-garage manors roosting atop the ridge are castles. And unlike your new manors strewn upon meandering labyrinths, those humble bungalows were tightly spaced upon a serious little right-angle grid just a few blocks square, a fleck of texture on that hot sea of scrub and tumbleweeds and dust stretching out forever, except where loomed the orange groves.

If Loma Linda was skimpy on buildings in those days, it was big on orange groves. And back then if you wrote about Loma Linda, you always wrote a lot about the orange groves, and how the mass of geometrically spherical explosions of lustrous blackish-green leaves studded with oranges loomed like a glacier, hard against the campus. You walked out of Burden hall and you were already in the groves. You would forever smell, in your imagination ever more strongly as the years rolled by, the headiness, the pagan headiness of the blossoms infusing the campus and the heads of medical and nursing students like the idolatrous incense from the Philistine groves inflamed ancient Hebrew youth. And among the orange trees were the smudge pots, black and ugly like Easter Island idols. Well, sure, there are still actually a few token groves around, but safely back beyond Barton Road, now the main drag. But no smudge pots.

So that’s it, our petite campus, the little San up the hill, the wee cottages and the 3-building inner city, everything within waving distance, and the orange groves. I could add the railroad running along the valley side of the campus. Those old locomotives were real steam engines, wailing the classic lonesome who-o-o-o-o all night, shaking us in our surplus army bunks in a Daniels Hall communal sleeping room. You got used to it. Though it thundered or chugged on through and most of the time didn’t even stop, the train is as much a part of Loma Linda lore as the orchards, and like the orchards was the main entertainment back then, that and volley ball, and the turning of pages of, say, Gray’s Anatomy, and sweat oozing from un-air conditioned pores.

It was quiet and it was hot, hotter than now, hellish hot, too hot for anything but study, and it’s a wonder anybody could. And small-town quiet. Hubbub aplenty came in the junior and senior years, the clinical years, when you moved to Los Angeles. To go there you drove sixty dusty, mostly empty miles on that two-lane highway, a less imposing thoroughfare than Barton Road is now, along tall, shaggy eucalyptus wind breaks, a few scraggly vineyards, past scattered hovels out of Steinbeck, too many stop signs but little traffic, on into the city, to the White Memorial Hospital. If Loma Linda had orange trees, the White had patients.

But for pandemonium like you had never known, unless you were a veteran returning from WWII, there would be the Los Angeles County General Hospital, then the largest building in Los Angeles, all 13 concrete stories swaying like a pendulum to earthquakes, all three thousand beds, and the barbarian hordes of tuburculars, alcoholics, cirrhotics, nephrotics, uremics, many psychotics but few neurotics, and we had polio and gunshot wounds galore back then, even occasional leprosy, and a house staff that seemed larger than the whole population of Loma Linda. Now that’s something I could write about.

That was the campus and that was Loma Linda at a point in history about half way in the century between what the founders bought and what we are now celebrating. A pleasant place, a small town, lovingly remembered. Charming, at least to old grads. But I can’t say it was picturesque. You wanted picturesque, you went to the Mission Inn or Palm Springs. In keeping with the humble town and the professor’s old overalls; simple buildings, practical, stuccoed boxes without extravagance or ramps for the handicapped, unclassifiable as to pedigreed architecture, hardly the gothic edifices of legendary universities. What our buildings lacked in splendor was more than made up for by the black-green perfection of orange trees and the dangling delight of oranges, and close behind us were the bare rolling hills casting long shadows in the evening, and, across the valley, the sharp mountains, blue and translucent in the clear distance, snow-embellished – unpretentiousness cradled in magnificence.

No-nonsense places where the young would sit and listen and learn medicine, not symbols to overawe, or TV stages, our stark campus structures never came close to the pages of Architectural Record, but for all that are the more honored in the pages to follow. As many of us would affirm, our humble buildings served their purpose at least as effectively as those of vaunted Theme Park Universities. May your newer pavilions and edifices, like the newly rebuilt 6-million-dollar multi-media Campus church, and those yet to be built, like the 58-million-dollar multi-media Centennial Complex, be so blessed.

* "San" is short for sanitarium, a sort of Victorian-era hospital, noted for natural remedies, mainly hydrotherapy, and for extended care which could last years, nowadays appallingly cost-ineffective if not downright illegal. Initiated in the 19 century when the sanitarium was cutting-edge, the Adventist hospital system started as Sanitariums. When acute care facilities were added the designation was accordingly amended, e.g. "Loma Linda Sanitarium And Hospital." The old "San" on the hill, mentioned above, is long gone but the building isn't. It now houses the Schools of Allied Health and Public Health. Now there are only acute care hospitals everwhere, without the San part (sans the sans, if I may.) But the ye olde "san" idea, especially hydrotherapy, heavy on the pampering, still exists and thrives -- called spa, from san to spa -- of which the Loma Linda University Medical Center, now a sprawling complex of structures for every known specialty and research field, has...none. The Mound City Chronicles tells all about this kind of thing.