Even as Constable, Turner, Bierstadt, Sisley, and Edgar Payne more or less invented landscape painting, Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter created landscape art photography. And what those pioneers had to endure doing it! Adams in Yosemite braved blizzards on a pack horse or in a model T with a boiling radiator on hairpin dirt trails, and trudged 4-foot snow drifts, shouldering a 8X10 view camera the size of a Victrola and tripod as big as field rocket launcher and crates of huge film holders, with a big black sheet over his head. Traveling lighter, Porter still lugged a 4x5 Linhof and clonky tripod and boxes of film holders and a complete chemistry laboratory through the uncharted rhododendron tangles of the Appalachians. Do you need a black sheet over a Linhof?

Even as Constable, Turner, Bierstadt, Sisley, and Edgar Payne more or less invented landscape painting, Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter created landscape art photography. And what those pioneers had to endure doing it! Adams in Yosemite braved blizzards on a pack horse or in a model T with a boiling radiator on hairpin dirt trails, and trudged 4-foot snow drifts, shouldering a 8X10 view camera the size of a Victrola and tripod as big as field rocket launcher and crates of huge film holders, with a big black sheet over his head. Traveling lighter, Porter still lugged a 4x5 Linhof and clonky tripod and boxes of film holders and a complete chemistry laboratory through the uncharted rhododendron tangles of the Appalachians. Do you need a black sheet over a Linhof?

So it remained for me to perfect the art of plein air landscape photography. Strolling teak decks with my Canon digital SLR in hand and a couple of compact flash cards in my pocket, I arranged to have the world’s most photogenic landscape, the Alaskan Inside Passage, delivered to me on a platter. The worst I endured was the TSA shoe strip, a sprightly breeze on the top deck, and a Charlie Chaplin baggy rented tux for the Captain’s dinner of Alaskan salmon en phyllo with wild mushrooms and caviar in a glittering dining room with best friends and soft music, and then the floor show. And I ran out of compact flash cards on the first trip. No sir, not on the second.

We did the Inside Passage twice, in 2005 and 2011, both times in June. It took two trips and two ships and two Junes to get the photos in this book. One ship was the smallest on the route, the S.S. (Small Ship) Yorktown Clipper (since defunct), puttering around Skagway and Juneau, sidling in among orcas, romping among the bergy bits like a puppy among squirrels. And the other was one of the largest and most opulent, the Crystal Symphony, marching down the Chatham Straight as ceremoniously as a provost at a graduation, scared away by the bits like a horse by puppies. And both times with the best of travel companions, Bill and Judy Doyle.

So here we are, the four of us, in the Prego Room again, at our favorite table. Oh goodness! Look at those peaks moving by, those clouds, those compositions! Oh, I’ve got to get this! “Excuse me, folks.” And I pop up and am away.

Just a pop-up away from magnificent peaks, clouds, compositions, table and sommelier, a cruise venue is the most marshmallow artistic experience an artist could dream of. But by the same token it presents an odd artistic disadvantage. It’s the foreground, or lack of it. The only foreground is that same flat boring water. You are deprived of all the handy foreground elements like the meandering stream Walter Palmer painted into his exquisite snow scenes, the happy little ravine or clump of sumac, the line of skewed telephone poles or stubby fence posts, the famous translucent backlit green wave and crashing breaker. Even a sprig of eucalyptus dangling overhead.

All the better. Naked stratified granite mountains listing terribly sink like the Costa Concordia into a disinterested sea; abstractly patterned peaks soar up without warning from the primordial liquid flatness; overlapping receding planes of translucent crystalline mountains, islands, peninsulas, each a different value and hue of blue upon the flat gray expanse; a mirror image faintly rippling or more flawless than the image itself, a la Maxwell Parrish, an upside down doppelganger; the wispy uncertain clouds against a bed of dancing, blinding laser sparks. Only that leitmotif could yield such surrealistic fugues, the artiest kind of composition. If done right.

Meanwhile where is everybody? Ganged up on the starboard side ogling orcas, is where they are. But this side is where the clouds and peaks and compositions are dancing!

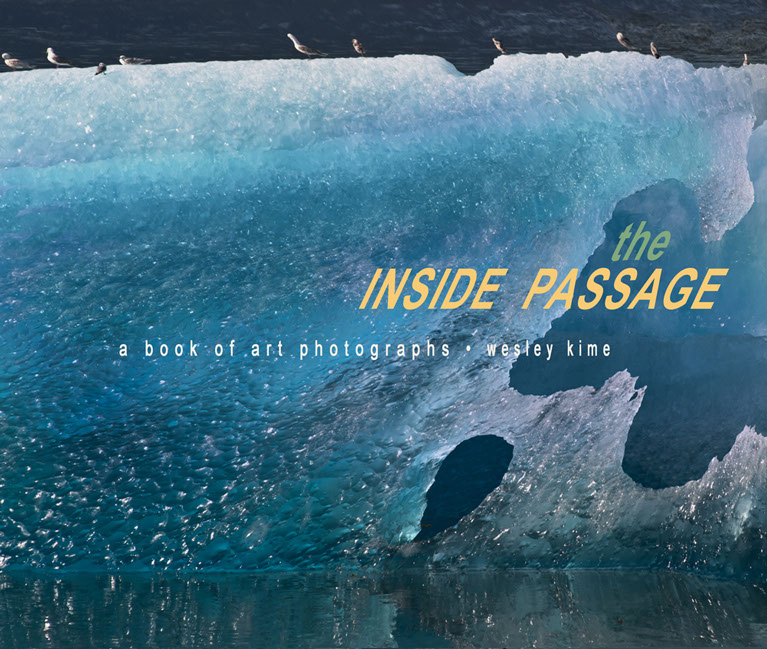

To see orcas, tail-whacking geyser-spouting orcas, is the goal and grail of the throng making this eco-migration, always on alert for the captain’s or staff naturalist’s announcement over the PA, “Orcas sighted off the starboard!” The orca is the signature wildlife of The Passage like the coon and pileated woodpecker of our old Bellbrook Ohio woods, the mosquito of upper Michigan, the leech of the Burmese and Wall Street jungles. But not for me. The bergy bit (Icebergus dinkus) is.

In their natural setting, in June, these cute little critters calved from glaciers are more like Slurpee than like real icebergs. Of capricious crazy shapes a la Pixar Animation Studios or, in the old days, the fin-tailed Cadillac; of an eerie color of fluorescent turquoise unknown to the Caribbean or Winsor Newton paints (synthetic phthalo blue comes close) and beyond the gamut of the Photoshop color space, itsy bitsy bergy bits are more arty to my eye than the sublime ice mountains patrolling the North Atlantic. I’d sooner photograph bergy-bit slurry than petit fours at the Captain’s gala. Or even glaciers – artistically if not geologically overrated, I think.

Meanwhile on the port side. Obsessed with composition, I am oblivious to where I am. But then so is everybody. A Lewis & Clark mapping expedition this was not, not for us drowsy retirees. Not a navigation chart in any hall and just a token map in the travel brochure no more informative than the logo. Google Earth shows every known taco stand but ignores topographical labels. Anyway I don’t own an ipod. Only after I got home and had collected my wits and images did it occur to me, where was this photograph taken? Can’t say. Unlike NASA or spy satellite images, mine are transcendent of this world, as seen by the Inner Eye liberated from time and place, thus all the more of the genre of art photos. Maybe my next Canon will automatically record GPS as well as f-stops and histograms and other metadata.

Into my mind they danced, these compositions, a storm of compositions — I feel them rather than see them — like a hacker mega-attack on Amazon.com, just about taking me down with excitement. Compositions excite me like porno an engineer in a cubicle. Well, sure, nice, they’re nice, it will probably be said, but not as awesome as a wildly Photoshopped, gauchely colorized, posterized orca or free-transformed eagle. I would hope not.

Composition, composition, composition. But something is missing. A totem pole. Nary a totem pole in this whole book. Bergy bits interested me more. Nor orca, no orca either. Don’t blame me: they were always on the wrong side.