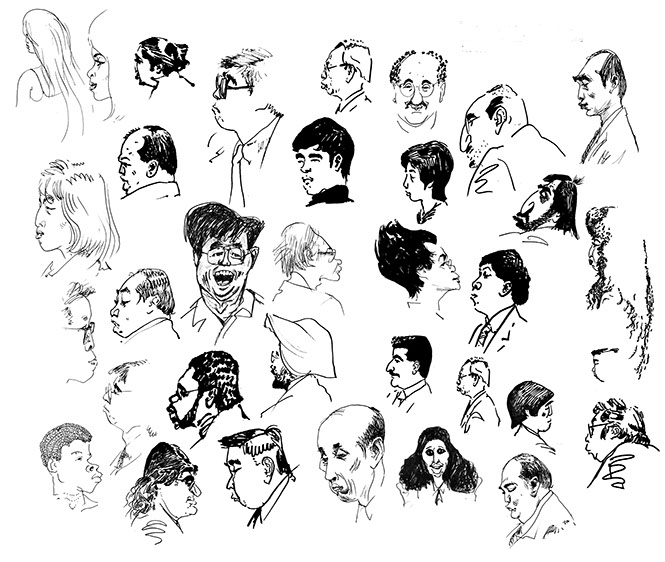

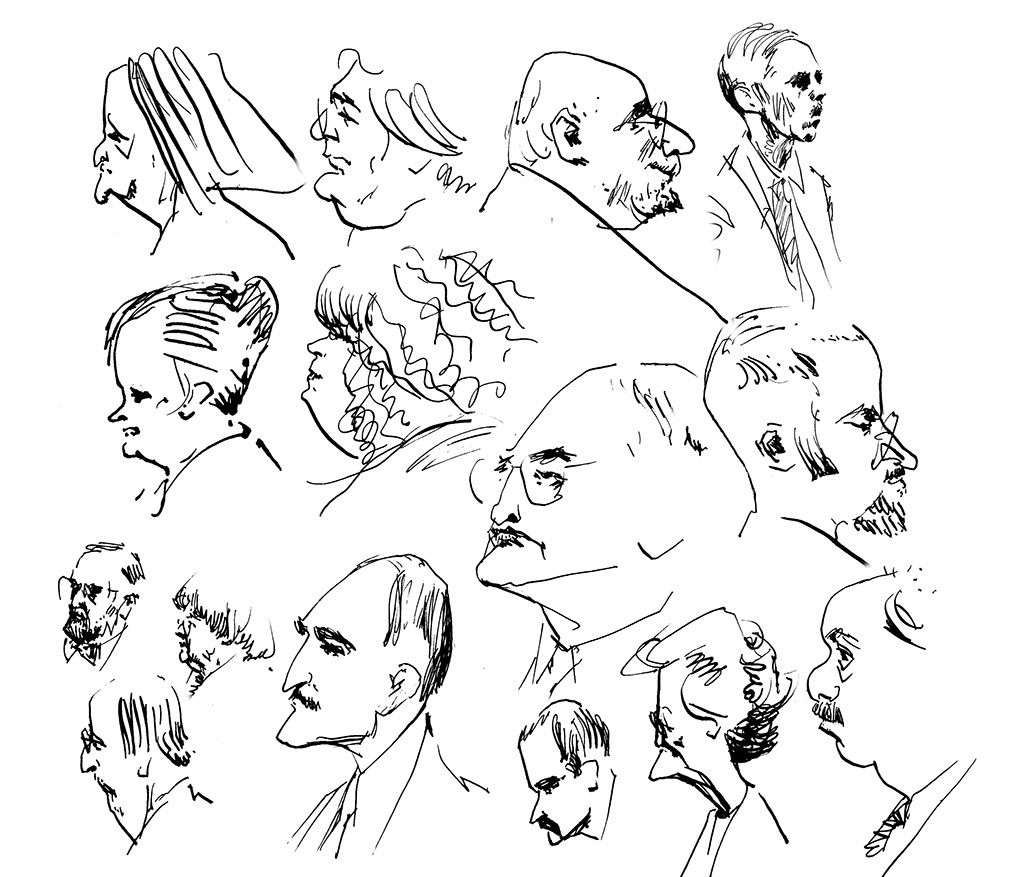

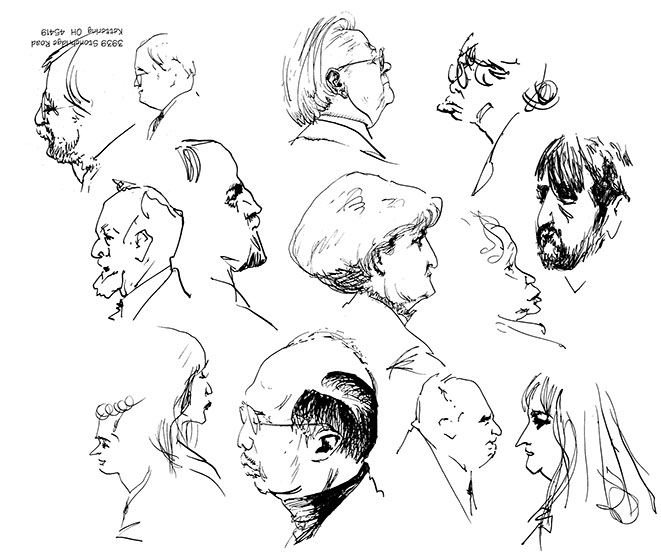

In the over 80 years of my 86 that I’ve been drawing flash fountain pen sketches – I mean from 15-90 seconds -- of classmates, and anybody else in the same room, I must have done at least 10 or 20,000 of them, my best guess. I never bothered counting. When I was in full swing, it was a rare lecture or conference or committee or church service that I would walk away from without 2- 8 more heads.

Looking back, I am not crowing over having drawn so many so fast, and so well. More puzzled than proud, I’m asking myself, why? Why on earth did I do that?

I had been drawing since before I can remember, probably since toddlerhood, just like all children do at that stage. Later when kids my age had graduated to more mature activities like baseball and hotrods and hanging out, I was still drawing classmates, as surviving 7th grade classmates, seasoned octogenarians now, tell me they still remember, though I don’t. Why would I remember? Drawing was so natural, like breathing or doodling or ogling girls, or like dribbling basketballs, which seemed oddly unnatural to me. When I was older it began to dawn on me that drawing people all the time was seriously non-mainstream. But by then sketching heads had taken on a life of its own and I couldn’t stop.

Normally conscientious and perceptive children (I’m not talking about rebels) go to school, and youth to medical school (which I did), to learn and also to make lifetime friendships of classmates. Learning I took seriously, maybe too seriously, but as to the kids around me, it never occurred to me to interact with them other than to get their faces on paper. People were put on this planet, I seem to have thought, for sketching, nothing else. Reviewing these sketches in preparing this essay, I have become aware, and embarrassed, that drawing their visages brought me closer to quiet joy than their friendship could have, or in any case did. I suffered some sort of autism, is my diagnosis, only partly facetious.

But heads, actual heads of classmates? Everybody knows that an arty kid sequestered in a classroom gazes out the windows and dreamily doodles pirate ships and knights in armor, or queens, or dragons and monsters, nowadays zombies, anything but what he’s looking at in the room, liberated creativity in action and the absolute proof of genius. Alas, I’ve never been able to gaze dreamily out windows like a normal genuis.

But early on I somehow knew that I was destined for greater art than doodley-sketchery. Someday, though it would not be in youth, or even middle age, I’d be advancing from quickie pen sketches to full-time full easel portraits, like Sargent. Sketches were simply exercises and preparation for the easel. And upon retiring from medicine at age 65 I finally did exactly that, switch from only sketches to mainly perfected oil portraits at the easel that took from days to months to finish. If I do say so, mine evinced a certain unique controlled bravura and a fearless flair for informality and an uncanny if not flattering likeness, thanks indeed to all those years and thousands of sketches, a preparation that professional portraitists cannot claim, and do not seek.

Early on, in my early and mid-teens, and suddenly serious about drawing, I went at it as a kid planning a career in art would, studying standard art-anatomy references and attending live model groups. I learned classic proportions of the body and head, practiced blocking in. I did finished drawings, not sketches, taking maybe a couple of hours, suitable for 1-man art-student shows, as did happen when I was 16 at Occicental College, taking premed. But when school and then my career in medicine took over my life 24/7, and my subjects were young or youngish classmates or committee-mates, sometimes drowsy but generally hyperactive in their seats, of necessity I segued from this classically finished, lumbering style to flash sketching of un-posed classmates, no time for blocking in, sometimes not even looking at the paper. Did that in my head.

Medical school turned out to be my de facto art school. At my “art school,” unlike the Ecole des Beaux Arts, or the Art Student’s League of New York, the subjects were not posed hired professional models (procured from the streets), but medical professionals oblivious of, or nonplussed by, the use I was making of them. Their poses were not of the classical atelier kind, e.g, throwing a discus, much less nude. Saw plenty of nudes along the way, but none open to, or fitted for (except to medical illustrators), arty pursuits.

And my subjects were not perched individually on posing platforms but usually seated in rows, or sprawled in pews. In class or church it’s awkward to wheel around to see a subject’s head face on. Thus many of my subjects are viewed from behind, with the back of the head disproportionately massive, and the chin and nose, even a bulbous one, are commensurately foreshortened and partly hidden by the seemingly bulging cheek. And where is the ear to be placed? I had to deal with perspectives unknown to, certainly rejected by, say, Van Dyke.

Setting up an easel and flailing big brushes are routine in art schools and may be de rigueur in Paris cafes, but awkward in pharmacology class at med school. There your drawing tool is what is in your pocket, usually my shirt pocket. At the beginning, in Med school, my pocket contained only my beloved brand new Parker 51, a gift from my dad. By the time I got to Ohio my shirt pocket was famously bulging with 2 or 3 kinds of fountain pens (flexible nib, wide-nib calligraphic, or my old Parker 51 filled exclusively, for nearly 70 years, with dense black Parker Quink ink), sometimes a roller ball pen but never a “ball point.” Plus an uncertainly pointy fiber tip pen, and a .5 mm Pentil automatic pencil with B leads. In St. Louis, in the nephrology research lab, I also used a ¼” square marker to sketch the experimental dog. When I was in my sixties my pocket was stuffed with all that plus a laser pointer and a remote controller for my hearing aids.

Believe it or not, I always tried to keep what I was doing covert. It never occurred to me to show off or be famous for sketching, which, come to think of it, is another oddity of mine. But how could my activity be surreptitious in medical school or executive committee? Who am I kidding? My teachers, professors, and committee chairmen all must have known my hand was busy with other than notes. They must have inferred as much from the way I’d suddenly be grinning for no apparent reason. Yet they countenanced it. And my doodling, which one would think would be distracting to me as well as others, didn’t seem to interfere at all with my grades (I was high school valedictorian and top man in med school at least 3 of 4 years), or even too seriously with my committee functions.

I achieved my peak output of sketches (some days over 15 heads), and virtuosity, in my middle years, from 35-65. Now an octogenarian, no longer do I paint, but I still sketch, though increasingly seldom. My hand is still as steady as a rock, but like a rock not so likely to dance and cavort as in days of yore. No longer do I go to the old sketching venues (classes or conferences or committees, airport lounges, restaurants), only church, and anyway nowadays presentations in such places, even church, are not just lectures or sermons but Power Points and videos and the ambient lighting is so dim I can’t make out the faces of people. Or is it that my eyes are themselves dim? In reviewing this series I take notice of my notes that a drawing was “drawn in the dark.” Sure couldn’t do that now. If my literal eye goes dimmer than my Inner Eye, that will be the sign of the end.

Flash Sketches